Setting the Table 2022 gouache & collage, 29.50 X 40 inches

How to set a formal table

With just a spoon, a bowl, and a pitcher

You can survive or set a formal table

But you'll need more than the alphabet

For a love letter or something besides the news

The clothes of the person you desire

And your clothes together in the washing machine While at home the ink dries on a landscape painting While searching has become researching

With just a spoon, a bowl, and a pitcher

You can survive or set a formal table

But you'll need more than the alphabet

For a love letter or something besides the news

And in the sky the stars of the Milky Way Flow and shine, their light falling on

The stupid stone lions in front of the museum As it falls on a lover so sweet and so pure

With just a spoon, a bowl, and a pitcher

You can survive or set a formal table

But you'll need more than the alphabet

For a love letter or something besides the news

2024 Joshua Edwards (for/after Julie Speed)

The Lamp of Painting

The artist in her studio

looks into an empty canvas. Stars fall. The desert was a sea. Where is the new allegory

that reaches for eternity?

So much of painting is thinking.

So much of life is standing still.

So much of love means being kind. So much sky is beyond the clouds. The art of arts is passing time.

She looks upon some pictures of the things that occupy her mind:

a skull for death and theater, a badger and a hare, a bird of prey whose prey is man, formations of geology,

a fish who seems too large to live, and shapes of distant galaxies.

An idea arrives as color

and her job is to bring it home. These hours are full of thinking too. The image emerges, slowly

then suddenly it’s there: a whim,

a wish, a dream that’s now a thing.

2024 Joshua Edwards (for/after Julie Speed)

The Lamp of the Sea

I remember the sea outside

my window: the sound, how it smelled, and the great presence of color

in a blanket that extended

far beyond the edge of our beds.

The sea lumps us all together:

waves are so many hearts beating in ripples on the sullen Earth.

It’s said the sea is most like blood for how they both reflect the Moon and boil beneath a bullish Sun. And it’s all alliteration,

with a clear message: life repeats itself just like the priggish sea.

I hate such pretense anyhow,

so full of salt it tastes like tears. Who wants to watch a reflection of the sky in a churning mess

of blues and black or greys and green? Half the world will never know it

and with that half I cast my lot.

I live a thousand miles away

from the water’s repetitions. I live a thousand miles away.

2024 Joshua Edwards (for/after Julie Speed)

Joshua Edwards http://architecturefortravelers.org/

Joshua Edwards is a poet, translator, editor, and occasional curator. He’s the author of a half-dozen books and his photographic projects have been the subjects of several solo exhibitions. The recipient of grants from the Fulbright and Stegner programs, as well as Akademie Schloss Solitude, he currently directs Canarium Books, and teaches at Pratt Institute and Columbia University.

Lynn Xu

Untitled

Driver of Clouds

Dispenser of Winds

It is the Earth

that turns

in the dead of night

while you are still alive

so slowly and at

once upon this Pinpoint of Anguish

Anguish sorrow- followed

and the Wheel

that rolls with little teeth all along the groove Earth’s

slow wagon

day after day on yesterday’s streets

Fear

following fear

Xu 1

in rippling

robes

through temple doors

raising All to shade

this World

is wrought by human

hands the work of human

hearts

by the light of our own burning homes

summer autumn winter

spring: unclose your shadows

hear our prayers

born in night with night-time things allied— come before we leave

describe us to the revelers

and name us

as we are

and when the Sun returns

where lifeless bodies are outspread

and hair

unbound

in mourner’s way

LYNN XU

Lynn Xu

SHANGHAI

Columbia University, Abigail R. Cohen Fellow

2024/2025

Fusang

Born in Shanghai, Lynn Xu is a poet and Assistant Professor of Writing at the School of the Arts. She is the author of Debts & Lessons (2013) and And Those Ashen Heaps That Cantilevered Vase of Moonlight (2022), selected for the Poetry Center Book Award, and co-translator of Pee Poems by Yang Licai (aka Lao Yang). She has performed multidisciplinary works at 300 South Kelly Street, the Guggenheim Museum, the Renaissance Society, and Rising Tide Projects, and her work was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson. She coedits Canarium Books. At the Institute, Xu will be working on a book of poems about the many journeys to Fusang—the mythical place in Classical Chinese literature that then became, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a figure of fascination for the Western imagination.

Rebecca Danelly

Compass: A Tarot Spread inspired by works from Julie Speed’s A Purgatory of Nuns*

1. South, where you’re coming from– After “To the Sea: *protection from: *Drowning, Pneumonia, Nostalgia”

You came on like a primordial monster,

like H.P. Lovecraft in polished boots and

ten-gallon hat white as your back-handed

compliments. You asked me to go swimming

as if I’d ever trust your tentacle

arms and bleach-toothed mouth. You told me you

liked my fancy words. I wondered out loud,

Don’t you have a PhD? Of course,

you corrected me, I only got

a DD but I’m the guy you need

to bless the water to dunk a sinner in.

You chuckled when I scowled, first at you

then at myself. Who was I to name

you chaff when I meant to cherish all my

sisters and brothers? But, I couldn’t reign

in my disdain. I knew by your jovial

smile, I was the Philistine and you,

the Pharisee.

2. West, what’s directly behind you – After Newt: protection from *Dyslexia, Nearsightedness, Illiteracy

You read the water as if it offered

silk sheets, a plethora of soft pillows.

Ready to recline in the pond’s still waters,

you waded in like a newt ready to spawn.

Your robes absorbed water, became heavy,

pulling you down as if to drown your

amphibian lust for Faith. Imagining

Jesus’s soles upon the sea, how he

strode lightly and called to his men, you sat

and barely touched your unchafed palms

to the pellicle between wet and dry,

your sacrifice ready but incomplete.

An eager newt nudged your blooming skirts,

black as the water’s depths. Unconcerned,

the wind chafed the lough’s mirror. You

looked up. A hawk dove into the trees.

You prayed Our Father. You prayed Hail Mary,

laid yourself down, and swallowed the pond’s

truth. Your surplice became a frond for triton

eggs, a nest for metamorphosis.

3. East, what lies in front of you – After Swallow : *protection from *Heartbreak, Disappointment, Recession

Receding in daybreak’s silver light

before the sycamore’s leaves burn

golden through your window, you see

the distant conflagration of trees,

flames making cinders of branches

and leaves, alighting the Book in her

left hand, her arm outstretched as if

to offer or refuse its truths.

She turns her wimpled head to eye

in disbelief the swallow soaring

earthward into granite hills

its bifurcated tail aflame.

Her surplice bears an ornate cross,

crosshatched by spear and maul.

Plummeting, the bird’s chest glows red,

its throat flushed cerulean.

As if her glance were yours, full of

surprise and ready to burn, you cough

in the morning light. Heartbroken,

you wish on her your despair.

4. North, The next move – After Serpent’s Tongue: *protection from *Hypocrites, Politicians, Preachers

We all know that the serpent in the Garden

spoke the truth, that Y____H’s slithering

tongue lied. Eve tested the air with her

mouth, tested the fruit with her teeth

and knew what was good. She lived. She

shared the truth with Adam. The mimosas

spread their tinsel-leaved branches heavy

with blooms and its magenta pom-poms

littered the verdant lawns. The fichus grew

taller than the Woman. The rubber trees shot

skyward. In the serpent’s coils, Eve sighed,

while Adam watched, unsurprised. They were

dates and pomegranates and bananas.

The fruit of the Earth. Holy. And

lascivious. The taste of Paradise. The scent

of lilies. They touched and were fecund. Ferns

in the undergrowth. They refused, they knew, and G-d

frowned. They sang their verses, unsurpassed.

5. Grounding - to be read South, West, East, North

After “Compass - *protection from: *Disorientation, Confusion, Moral Lapses”

Joe Sawyer from the Amon Carter studio visit. The painting he's singing to is named Siberia.

Lucky

2012 oil on panel, 20 x 24 inches

Lucky

by Andrew Colarusso

Arguing over slight of hand while

it rains enigmata and the world is

hung uncomfortably in the balance

seems just so [she pauses] petty.

No matter the source of slight [she

corrects herself] light—shadows, it

would seem, display a tendency to

ward schizophrenia. One might find

at least two parts in every shadow,

umbral and penumbral absence,

submitting their lives over limina

to larger sovereignties, dispossessed

of themselves, rending a portion of

ipseity against what holds the rope

guying fear. Are you anxious [she

asks] Don’t be. He was a rabble-

rouser. And like all guilty men he

lost his head long before you or I.

You know that, baby. We weren’t

using those chargers anyway.

#Ekphrastic poem by Andrew Colarusso

The Murder of Kasimir Malevich # 5

A. M. HoMeS

Do You Hear WHat I Hear?

He HeArS tHe CAr beFore SHe SeeS it. tHe Sound draws her to the window. It’s dusk, the headlights are on: two eyes staring down the long road. When they hit a bump, they vanish mo- mentarily as if blinking. The twilight sky is a pitch-perfect blue that hums. In front of her house, the late-model black sedan slows, then parks. No one gets out. She peeks from between the Venetian blinds. When she pushes down the blind to get a better look, the old metal bends with a loud crack, startling her. The car’s headlights are still on, staring down the street like someone lost in thought—daydreaming.

Maybe they are not who she thinks they are, maybe they are here for some other reason, maybe it has nothing to do with her. But it’s not every day a late-model car pulls up outside and just sits there.

She gets binoculars. By the time she’s back at the window, the headlights are o , but now the interior light is on. She spies two men wearing suits and black hats. The driver is resting his arms on top of the wheel and the other one is reading a newspaper. She focuses the bin- oculars—reading over his shoulder, so to speak. Sports. She watches for a few minutes, noth- ing happens. She goes back to what she was doing—whatever that was. She can’t remember. Twenty minutes later when her doorbell rings she’s caught o guard and has depilatory cream on her upper lip, defoliant she calls it. She wipes o the Nair and goes to the door.

“Who is it?” she asks.

“You called,” one of the men says.

“I called two days ago,” she says.

“We’re not full time,” the man says.

She opens the door. “Well, I thought it might be you. I saw the car pull up, but then no one

got out.”

One man gestures toward the other. “He was listening to his radio show.”

“You had the interior light on,” she says.

“So I could read the paper. And besides, I don’t like to be left in the dark.”

“Come in,” she says. The men check left and right before entering. She spots her binoculars

on the oor and kicks them under the sofa.

One of the men takes his hat off; he’s got another hat on underneath. She wonders if he’s Jewish, or undergoing chemotherapy. “I’ve got a head cold,” the man says, feeling her stare.

“That can happen just about any time of year,” she says. “Are you from around here?”

“Not far,” he says.

“Not from here,” the other man says. “It’s easier for us to do our work if we’re not natives,

not too familiar, we’re less likely to miss a clue if it’s all new to us.” “Have a seat.”

The two men sit side by side on the edge of the sofa.

“How’s the weather been?”

“O and on,” she says. “Not so long ago we had an odd one—there was a rushing sound,

folks said it sounded like a twister, except it was bright white, like a snow cloud in an otherwise empty place, it blew through a shield of hail, like a single plate of shattering glass, a lot of sound, hailstones like baseballs and in ve minutes the sky was clear again.”

“Atmospheric bloat and purge,” the taller, thinner of the two men says.

“And last Thanksgiving we had that freak snow cone that dropped crushed ice every-

where.”

They nod. The taller of the two reaches up over his shoulder and, without turning his head,

plucks a bug out of the air and squashes it bare-handed.

“Would you like a tissue?” she asks.

He takes a handkerchief from his pocket and deposits the dead bug into it, refolds the hanky

and puts it in his breast pocket. “I’ve got it,” he says, patting his pocket. “Must have got in when you opened the door.”

“How about a cup of tea or a cookie?”

“You wouldn’t have a Dr Pepper, would you?”

“Yes, I do. I’ve got 100 percent authentic Dublin Dr Pepper—oldest Dr Pepper plant in the

country.”

“And the only one still using Imperial Pure Cane Sugar—makes a di erence.”

“Make that dos Dr Pepperos,” the other man says. She notices that he’s got a foreign

accent.

She dips into the kitchen and returns with two tall bottles of Dr Pepper—she pops the tops

and hands a bottle to each man. “May I ask your names?”

“Serge,” the one with the foreign accent says.

“Katherine,” she says, tapping her hand to her chest. “But you already knew that from the

call.”

The men sip their Dr Peppers in silence.

“Mumm,” the other man nally says. “Tom Mumm.” He takes another sip and looks around the room. “Is that one of those radioshack pictures?” he nods towards a painting on the wall.

“How do you mean?” she asks.

“Radioshacks, the psychological test. You look at it and it tells you if you’re nuts or not.” “Actually, my cat made it—I had a cat who liked to paint. I’m not sure how she picked her

colors but they turned out pretty good. She passed a couple years ago, but her work lives on, I could show you a video of her working—they made one for public television.”

“It looks like owers in a vase,” Serge says.

“I was going to say spiders leaving the web,” Tom says.

A cat comes out, icks his tail against Mumm’s leg, Mumm cries out. “What cat is that?” “It’s the neighbors’—they’re never home so it hangs out here. Doesn’t paint though, just

eats and poops. I gave it a litter box with antennae, rabbit ears, it’s a little joke between me and the cat.” Katherine is the only one who laughs.

“And that?” Serge asks, pointing to something hanging o the wall.

“The hand of fate,” Katherine says. “I made it myself. I poured hot wax into surgical gloves and let it cool.”

“Unusual owers.” Mumm nods to the blue carnations next to the hand of fate.

“I made those too—with food coloring. I like them because they exist nowhere in nature. That’s why I like it here—this part of Texas is like no other place in the world.”

Serge chortles. “Certainly very di erent from my Russia.”

“How did you come from Russia?” she asks.

“On an airplane.”

She’s not sure that was the answer she was looking for but lets it go.

Serge touches the fabric on her sofa. “Opulent,” he says, practicing his pronunciation.

She smiles. “I go to Europe every year during the month of July—it’s too hot here, and ev-

erything there is on sale, you can get bits and pieces. I’m a gatherer. I gather things.” “And that’s how you make a living?” Mumm asks.

“I give piano lessons.”

“What’s the cat’s name?” he asks.

“Dusty, short for Dostoyevsky.”

“Is that Polish for something?” Mumm asks. No one answers. “What is this place anyway?” he asks, suddenly crabby, put out, defensive as though he embarrassed himself with the Polish joke. “Where the heck are we?”

“It’s a stop on the road to nowhere,” she says. “They used to call it Tank Town—a water stop for the railroad. They say the town was named by a railroad engineer’s wife who took the name

from The Brothers Karamazov, others will tell you the town was supposed to be Martha, but the person who named it had a speech impediment and so it came out Marfa, and there is a another faction who point to a character in a book by Jules Verne. Any which way it’s the stu of ction,” Katherine says. She once again glances out between the blinds. “So is that your car out there?”

“Why not leave the questions to us?” Mumm says.

“Your lights are on.”

“Shit.” Mumm opens the door, steps outside and claps loudly, dogs bark—the lights turn o . “He’s always up to something,” Serge says.

Mumm comes back into the house, closes the door and locks it.

She is suddenly a little nervous. There’s a shift in his demeanor. “We came about the call. We

have reason to believe that he’s been here before, that he likes Texas.”

“How long have you lived here?” Serge asks.

“My whole life. My mother’s father was an early adaptor, he bought land a hundred years

ago. My father was stationed nearby, learned to y here during the war. My mother too, she was a military pilot—wASp. I was a late baby. My parents were already divorced when I was born, I was created after the fact. Best sex she ever had is what my mother told me, that’s why she never got pregnant before, it just wasn’t good enough to make a baby.”

“That isn’t something a mother should tell her child,” Mumm says.

“‘Should’ isn’t the word to use, it implies an error has occurred. If she hadn’t, then I wouldn’t, if you know what I mean.”

“About the call?” Serge asks. “You got the call.”

“Yes.”

“Where were you when it happened—were you asleep or awake?” Mumm wants to know. “I was in the kitchen cooking.”

“Could we see the kitchen?” Serge asks.

She leads the men into the kitchen.

“That phone there?” Serge asks.

She nods, yes.

“Yellow, wall-mounted, Bell System mid-1970s model. Heavily kinked extra-long cord.”

Mumm talks, Serge takes notes.

“I like to talk while I cook,” she says.

“I haven’t seen one of these in a long time—still works?” Mumm asks, suspicious.

“Never fails,” she says.

“Is that blood?” Serge points to something on the receiver.

Mumm licks the phone. “Tomato sauce,” he says. And then wipes the phone with a cloth

from his pocket.

“My grandmother was Italian,” she says.

“Mine too,” Serge says.

“Was the room like this before the call or was that something that just happened?”

Mumm gestures oor to ceiling, indicating the glossy white macaroni decoupage that covers everything.

“I worked on it for years,” she says, pulling open a drawer and showing the two men her glue gun. “While things cooked, I glued and then I painted. It’s pretty durable, every now and then it gets a chip and I repair it. Long ago, when I was in kindergarten, we made macaroni pencil cups for our grandparents, I still have the one I made for my grandmother—glued macaroni onto a Campbell’s soup can and spray painted it gold—Andy Warhol may have been the rst one to the bank but he was not the only one who saw gold in them there hills.”

“Going back to the call, what time would you say it came in?”

She shrugs. “Sixish.”

Serge sprays the phone with something he takes from his pocket.

“Are you dusting for ngerprints?” she asks. “It wasn’t a burglary, as far as I know no crime

has been committed.”

“We have to investigate,” Mumm says.

“Actually I’m germ-phobic and you saw what happened before—he licked it,” Serge says. “Taste buds are smart buds,” Mumm says.

“It’s Listerine,” Serge says, spraying and wiping, spraying and wiping. “I ran out of Purell.” “When you called us, where did you call from?” Mumm asks.

“I called from here, I was in a panic, well, not really a panic but in a state. I certainly called

from a state.”

“Let’s go back over it from the beginning,” Mumm says. He puts his Dr Pepper down on the

kitchen table and opens his briefcase. It’s soft-sided, more like a large ziplock bag. She didn’t realize he’d been carrying it with him. She hadn’t noticed it at all. And yet, it’s xed to his wrist with a cable tie almost as though handcu ed there. She can’t help but stare, it’s awkward as Mumm twists his hand around trying to open the bag. She’s not sure if she should o er to help or not.

He catches her eye. “I lose everything,” he says. “Been that way since my mitten clips.” He nally gets the bag unzipped and takes out a notepad and a heavy red leather-bound book, puts the book on his lap, notepad on top, and then withdraws a ballpoint pen from his pocket.

“You don’t have to write on your book, you can use the table,” she says.

“That’s OK,” he says, “It’s the Good Book. I carry it everywhere.”

“Not only does he carry it—he sells it, in a ne leather binding. We’ve got a trunk full,” Serge

says.

“I’ve got the book as well as some nice hairbrushes if you need one, from my previous position.”

“You were a hairstylist?”

“No,” Mumm says. “Door-to-door sales—in the evenings after work. If you need anything later, when we’re done, we’ve got it all in the trunk. OK, so you don’t have caller ID, did he iden- tify himself?”

“Not overtly,” she says. “At rst I did think he was trying to sell me something—I just couldn’t gure what. He never seemed to zero in on a particular product.”

“Did he speak of a certain kind of hunger, any mention of desire?” “No.”

“Did he swear at you or use dirty or abusive language?”

“No.”

“Speak about himself as the father of man?” Mum asks. She shakes her head, no.

“Any mention of a position you should assume?”

She is confused.

“Down on your knees?” Mumm asks.

“Did he seem in any way ironic, amused, mocking?” Serge asks before she answers.

“No.”

“Did you enjoy the conversation, did it leave you feeling lifted or otherwise transformed?” “I felt OK at rst, a little surprised, caught o guard, and then later it started seeming

stranger and stranger.”

“About how long a conversation was it?” Serge asks.

“I really don’t know—it was like everything suspended during it.”

“Ten minutes or two hours?” Mumm asks.

“Yes.”

“Did he mention speaking again in the future?”

“He neither ruled it in nor out.”

“Do you feel you know or understand him any better and/or that he had a deeper under-

standing of you?”

“Not so much.”

“Was there a confessional aspect, did you tell him secrets, things about yourself that no one

else knows?”

She shakes her head.

“Any sense of menace or threat?” “None.”

“Did the subject of plagues come up?”

“No plagues.”

“Any mention of wrath?” Mumm asks. “Judgment . . . a sense that we were getting it wrong—

disappointing him?”

She shakes her head.

“Do you remember anything about the tone of his voice, did he sound annoyed, amused,

intrigued?”

“Mild. I would say he sounded mild.”

“How were things left, was there a sense he’d call again now that he’s got your number—did

he mention getting your number from someone, having some kind of connection to you?” Serge asks.

“Did you get the feeling he’s done this kind of thing before—or are you the rst?” “Was there any kind of tone at all, beyond omniscient, beyond neutral?”

“I’d have to call it apologetic.”

“Did he ask for anything—were there any demands?”

“He wanted nothing.”

“Were you frightened by the call—did you feel it told you something, compelled you to a certain behavior? Excuse the pun, but did it feel like a calling—as in, you were called upon, that you were being asked to do something?”

“After the conversation did you have the sense that all things are one?”

“Does he have any kind of memory—did he recall or refer to past incidents, or visits?” “Did he refer to himself as a creator?”

“Did the person you spoke with give you a name or otherwise indicate how he liked—I am

assuming it was a he—to be identi ed?”

“He seemed to think I already knew who he was.”

“Did you star 69 him?” Serge asks.

“Pardon?” she says.

“Skip the question; you can’t star 69 from a dial,” Mumm says, rebuking Serge.

“You have to know when not to ask a question. You have to learn the meaning of n/a—not

applicable. Or irrelevant.”

In an e ort to interrupt Serge’s dressing-down, Katherine injects herself into the conversa-

tion. “I have a princess phone upstairs in the bedroom. It’s a push button.”

“But you’ve used the line,” Mumm says.

“Yes.”

“Drop it, let sleeping dogs die,” Mumm says. “OK, so just to review. You were in the kitchen

when the call came.”

“Actually, I think I was in the bathtub, I heard the phone ringing, I got out and walked drip- ping across the oor.”

“I thought you said you had just come in the door,” Serge says.

“I had you in the kitchen cooking macaroni and glue,” Mumm says.

She points to the hot tub just outside the kitchen window in the yard. “I was soaking in it.

Are you nding my story so inadequate that you’re making one up for yourself?”

“Bad habit,” Mumm says. “We get ahead of ourselves, ll in the blanks. OK, so you came in wrapped in a towel, ushed from the bath, the phone was ringing, you answered the phone and

dropped the towel, all eyes were on you.”

“Hello?” she says, ba ed.

“I think you changed your channel and started singing a di erent tune,” Serge says to

Mumm.

“Did I? My apologies. They used to say I had an 8-track mind. ‘Tom Mumm,’ my mama used

to say, ‘I’ll never understand what goes on in that 8-track mind of yours.’”

“It’s OK,” she says. “Maybe I don’t really know where I was. Maybe I was lost in thought. It’s not like when the phone normally rings you stop to think—where am I?—before you answer it.

The call, the oddity of it, was so overwhelming that in truth I forgot everything.”

“Are you a person of faith?” Serge wants to know.

“I never dropped the towel,” she says. “Ever.”

“Do you have a religious a liation, spiritual practice or some kind of habit along those

lines?”

“I would describe myself as a person of thought—a thinking person but not a joiner. The

last organization I ever belonged to was the Brownies and that didn’t last more than a couple of months. I don’t like activities that involve more people than a poker game. When I was young, I did think James Dean was a god and I did hope to be an actress. I even performed a bit. I took tap dancing. I danced in a show.” She stops to catch her breath. “I once had a boyfriend who’d been injured by the same car that killed James Dean.”

“The little bastard,” Mumm says.

“Dollar in the swear box, dollar in my pocket,” Serge jumps in. “You promised to watch your language.”

“That’s what the car was called, The Little Bastard,” Mumm repeats.

“How many times are you going to say it?” Serge asks.

“It was a rare silver Porsche Spyder, the car that killed him.”

Mumm and the girl are quiet for a moment, heads bowed in grim remembrance. “So what did you do immediately after?”

“I phoned my mother. I wanted to see if my phone really was working and I wanted to tell someone.”

“And did you reach her?” Mumm asks.

“She was out playing mah-jongg and didn’t call back until the next day.”

“Did you tell her about the call?”

“Not in so much detail. I mentioned getting a strange call, she thought it was most likely

from someone I dated long ago—one of the boys I liked but she didn’t, I reminded her that I was the one who got the call, not her.”

“Why did you contact us?”

“I thought you might know something, like if it was a prank or if it wasn’t. And I thought you would believe me.”

“Oh, we believe you, our belief is not the question.”

She opens the fridge and takes out a bowl of cherries. “Would you like a cherry?”

“Cherries are out of season,” Mumm says.

“A friend FedExes them to me from where they are in season.”

“I could never tell a lie to a cherry pie. That’s how we learn English in Russia.”

“There was a kind of simplicity to the whole thing. The only thing that felt ‘o ’ was that he

said ‘one plus one equals one.’ I didn’t want to be the one to correct him. I think he meant that ‘I’ is one, which is perhaps a di erent concept from something we’re familiar with. He also spoke about the importance of personal cleanliness and he talked about tolerating contradiction, the idea that something is and is not all at once.”

“I guess it’s about how you see things,” Serge says. “Through whose eyes, in what world, et cetera, et cetera.”

“Do you feel you have exclusive access to something? Do you consider yourself a chosen person?” Mumm asks.

“I’m torn between thinking he is something we create to keep ourselves from being very nervous and lonely and something that actually exists.” She glances out the window.

“You’re a ower,” Serge says, out of the blue. Her skin is delicate, her pores large, like swim- ming pools, like black tar pits. “It must be hard to keep yourself so beautiful,” Serge says.

“Two egg whites and ten minutes,” she says.

“What?”

“The egg whites tighten the skin and pull the dirt out. I am not what you assume,” she says.

“And you no doubt are not who I think you are.”

“Why don’t we begin from there—admitting that we know nothing, and that our assump-

tions will get us in trouble,” Mumm says.

“Are you alone—are you ever alone?” Serge asks.

“I stand before a mirror questioning myself,” she says. “I ask, what do people here want? I answer, a connection, con rmation that who they are and what they believe has a place.”

“Are you married?”

“Is that part of the investigation?”

“No, I was just wondering.”

“Well, I was going to get married, but then I didn’t—I broke it o and I was heartbroken—

that’s when I redid the upstairs bedroom. You can go look at if you like, I wanted something warm and old-fashioned, like the inside of an Easter egg. Everything here is homemade. I like the feel, the weight of the human hand in my everyday life.” The two men nod, appreciatively. “How much does what you’re just wondering a ect the questions you ask?”

“That’s a question you have to answer for yourself, about our obligations to each other, about what we expect and hope for in our contact and communication with each other,” Mumm says. “According to the phone company, you had no call that evening,” he goes on. “What kind of equipment did he use? And why would he have used the telephone when he could just speak to you out of thin air and be perfectly audible?”

“I think he was being discreet. He said he was somewhere and that he’d been thinking about things. Why don’t you tell me a bit about yourselves—how you ended up being the guys who came here, how you were sent to me—who are you and what do you do?”

“The rst thing you need to know is we’re real—100 percent authentic. You can look us up on the Web, Phenomena Police, we’re active duty o cers who investigate calls involving para- normal activity and other phenomena.”

“Are you a police o cer?” she asks Serge.

“In Russia we have our own techniques which vary according to the situation. Here I am try- ing to pass the regular test. There I was doing a di erent kind of work.”

“Like what?”

He makes a gun with his ngers and pulls the trigger. “Bang, bang. Here I have no arms.” He shrugs.

Mumm is sweating. Perspiration is suddenly beading on his forehead. “Must be hot,” she says.

“Depends.”

“Where do you get a suit like that?”

“Mail order. It’s custom, a single suit you wear year-round—got places to put ice packs in and a zip-in eece liner. And it’s water-resistant, not waterproof, but resistant.” He opens the jacket and shows her the inside, which is lined with pockets. “Comes with the ice packs. They say you can wear it anywhere from funerals to football games.” He plucks a stick of Doublemint

gum out of one of the interior pockets. “On occasion I’ve been known to use the pockets for other things. Look, I think we’ve gotten o to a poor start—may I ask for your phone number, and would it be all right if I called you sometime?”

“You can call, but if I don’t pick up leave a message, and NO hang ups.”

He nods.

“What about me?” Serge asks. “He jumped in there, but I was thinking the same thing, I was

thinking I’d like to ask you out.”

“First come, rst served,” Mumm says. “Finders keepers, losers weepers. Did they teach you

that in Ruskie spy school?”

“Are we done here?” she asks.

“I think we’re wrapping things up,” Mumm says. “We’re in touch, so you be in touch.” “Where do you go from here?” she asks.

“To get a bite of dinner,” Serge says. “And during dinner we go over our notes, we begin to

draft our report. Would you like to come with us?”

She blushes. “Thank you, that would be lovely,” she says. “Just let me get my coat.”

AS tHey’re leAving tHe pHone ringS, tHey All Stop in tHeir trACkS. “What should I do?”

“Let the machine get it,” Mumm says.

“I can’t,” she says. “I was lying, I don’t have a machine.” She hurries into the kitchen and

picks up the phone in the middle of the third ring.

The two men stand in the living room, hats on, ready to go.

“Hello,” she says. “How are you? It’s good to hear your voice again.”

Military Science

2000 From Alters of My Ancestors. Gouache, acrylic, and collage on board. 30 1/4 x 30 1/4 inches.

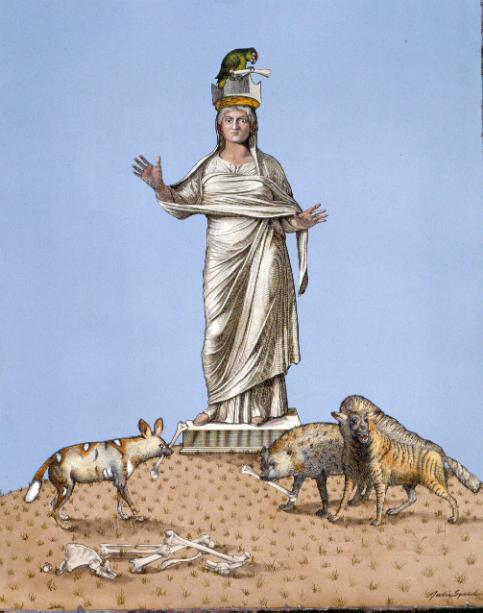

Vito and the Hyena Queen

Hyena Queen— for Julie Speed (and Vito) by Michelle Miller

I’m sick of chucking sticks for this pack

of lip-lickers.

I’ve thrown

my last bone, yet still they skulk

at the hem of my skirt, lurking

in the twilight of my noon-lit shadow.

Lovers, of course, are deterred

by all this blood. Except by muzzles,

my underbelly goes

un-nuzzled. All my shoes are ruined.

Was it just last March I decided

I looked sharp in bite marks?

Now I long for a single nipless

kiss. To spoon without scruff

up my nose. A bed clean of leaves

and leftovers. Lettuce.

In the beginning I couldn’t resist

all the bowing and crouching, this

smirking congregation swift

with hot gifts and songs like clock-

work. Never lacking for lunch

or lullabies, a girl could grow

attached to this lathe of cave,

loll stinking in its grip for days,

dosed on liver.

My mother’s

mother had a taste

for sweetbreads. I, too, know

to be thrilled by gizzards piled

fresh at my feet. More than enough,

it’s finally too much.

Have I forgotten the sun,

laundered scent of sky,

that crisp silence behind

the buzz of flies? Time to stand up,

shake them off.

Make a break for the trees.

Diminuendo

2003 oil on panel

The Intercession

1998, oil on panel 22 x 30 inches, collection of the artist

Beatifying the Animals by Michele Miller

A couple of times a year a church lady would come and try to convince us to join her religion, which said that only 144,000 souls would be allowed into heaven…. I asked her what about the souls of animals, and she answered without even a hint of doubt that she was quite sure they never went to heaven. — Julie Speed, on painting The Intercession, from Queen of My Room

Once dewclaw accumulated into opposable thumb,

how could we not start gesturing?

Like deluded prestidigitators, we believe a sign

of the cross etched mid-air conjures

just as solidly as a single digit sawed across

the throat. We bang the gavel because

it has a handle. We classify. Relegate. Unlike

the hound, unlike the heifer, we can finger

the equal number of letters

in salvation and slaughter,

point with parallel dexterity

toward the davenport and the abattoir.

Our thumbs go up.

Our thumbs come down.

Sitting in barcalounger judgment

with the footrest flipped up, determination

is easy to swallow if interpreted in terms

of appendage: He who holds the salt shaker wins. Our soul’s evolution reverses

in the parabola of t-bone thrown from fist

to dog-jaw. I fling, therefore I am…

Soon we are apes saying it.

And who can blame us

for not beatifying the animals?

Tossing out the cow heart that could not

muscle us to love it,

waving away the backyard mutt

congealed to tow chain, discarded

like the mangy couch she’s bound to,

we are free to walk the staircase

up to heaven on our hands.

Tea

1999 oil on panel, 22 x 30 inches. Collection of Tim and Nancy Hanley