MODERN DRUMMER

AUGUST 1983

FEATURES

Fran Christina's T-Bird Rhythms

By Chip Stern

The Fabulous Thunderbirds are the real thing alright. Hailing (both literally and spiritually) from Southwest Texas (Austin, to be specific), the T-Birds seem to sum up the earthy spirit of the entire Gulf Coast region, playing axle grease fried blues and roots rock ’n’ roll with the kind of outcast authenticity that can only be learned, not earned. From the tops of their Wildroot heads, to the pointy-toed tips of their feet, guitarist Jimmie Vaughn, electric harpist and vocalist Kirn Wilson, bassist Keith Ferguson and drummer Fran Christina exude commitment and no-nonsense enthusiasm. Their music seems to have chosen them every bit as much as they chose it, and one can half imagine them pickin’ their teeth with barbed wire after chowing down on a hearty meal of barbequed armadillo and cactus fritters, before draining a draught of thirty-weight and packing up their grip on the way to another party, in another bar.

All of which is captured with spooky vehemence on their last Chrysalis album T’Bird Rhythm in a winning collaboration with producer Nick Lowe. And so strong has been the word-of-mouth on this band that Carlos Santana himself brought them onboard for his latest solo album, so that he could “feel the earth underneath him.”

Which is why it came as something of a surprise, when I finally met drummer Fran Christina, to discover that, in spite of the roots authenticity of his upbeat Texas shuffle on “Extra Jimmies” (from their earlier Chrysalis outing What’s The Word), he hails not from the physical state of Texas, only from that state of mind.

Christina was born February 1 1951, in Rhode Island, but, as he puts it, “Musically, I never left Texas. I’m just a product of everything I’ve ever listened to, from Chicago to New Orleans to Texas. And most of the bands I’ve played with, especially Roomful Of Blues, Asleep At The Wheel, and the T-Birds, have reflected the sound of Texas r & b to one degree or another.”

Kind of a strange buzz for a young man to get living in Rhode Island, hardly a hotbed of the blues. “It was strange, now that you mention it,” Christina reflects. “It was a freak because we were playing music that nobody else was back then, and I have to credit Duke Robillard with that for bringing me out. Him and my brother. They were record hunters, and there were also a couple of good radio stations back then that played rock ’n’ roll, rockabilly, r & b and blues; a station out of Providence playing the stuff that we all gravitated towards. I think the first real buzz I got off of anybody was Muddy Waters and Elmore James, and it just went on from there to people like Rockin’ Sydney, T-Bone Walker… you name it.

“Actually, I have to take that back, about the first things that grabbed me. I was younger than that. You see, I grew up in a Catholic family. I used to go to my grandma’s house on Saturday night and stay over there with my cousin so that I could get up early on Sunday to go to Mass with her. But there was this Negro Baptist church down the street, and they all sang and got off, great gospel. So me and my cousin would go down there after Mass to check it out every Sunday; I mean, if my parents ever found out they would’ve killed us. Then we started going in the church. Oh, man, it was something the way they were getting down; it was just sonic. And that was probably the very first thing which turned me onto music.”

And that big beat, with everybody slamming their feet down on the church floor in unison.

“Yeah,” Christina smiles, “that was the whole deal. And it all came back to me later. What I just described happened to me when I was like seven or eight, then it started coming back to me when I began hearing all this r & b and blues. I started hearing all those sounds again, you know, Ray Charles and all that, and I made that connection and realized that’s what I’ve been hearing all along, that it was all the same. The hard blues, the rockabilly, the gospel, the r & b, the rock ’n’ roll. All of it came full circle and I realized where it all stemmed from. It all fit, and I haven’t had time to think about it since. I’ve just been doing it.”

Thus, without benefit of British midwifery (having American r & b fed to us by English bands), Fran Christina entered a musical continuum as rich and as varied as the people who make up America. “It’s funny, isn’t it,” he muses. “It keeps coming back and hitting ’em right in the face. It just blows my mind; I can’t understand why they want to deny it.”

So with that big beat echoing away in the back of his mind, Christina was drawn into the popular music of his day and its blues roots. But why drums?

“Well, you know how it is when you’re 12 years old. You go around banging on things, right? And then your older brother, who you really idolized, plays guitar with his grease-monkey friend, and they say ’Come on, we need a drummer.’ So they got me a pair of sticks. We used to be working the night shift in this guy’s garage, and we’d set up a bunch of oil drums, and they’d hook up their amps,” he laughs. “We’d do covers of Everly Brothers stuff; Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker. Which sounded pretty good on oil drums.

“Afterwards, I was in my little cover band in the bowling alleys. That was my pre-musical period from 12-14. You know, covers of “Get Off Of My Cloud,” “Wipeout”… bowling alley music. When I started, I had a set of Winstons, you know, but then my cousin had a boyfriend who had a beautiful set of Slingerland Radio Kings, and I wanted those bad. That was like my dream kit, so he was giving it up, and he sold me all his drums, hardware, cases and cymbals for $200. Beautiful cymbals, too; I had those for a real long time, until they were stolen on my wedding anniversary. There was this big 22″ A. Zildjian medium ride; really nice, even tone; good ping to it; and no big buildup, until you hit it in the right spot for that great big backbeat/r & b kind of thing… you know, where you want it to build up like a wave. Yeah, and a 20″ A.,” he continues digressing wistfully into his lost cymbal bag, “and 19″ and 18″ K. Zildjian crashes, and a 14″ K., that was a Turkish K., that was the neatest little crash/splash you ever heard it was so fast and dark. God, they were just great. I haven’t been able to find any cymbals that good since.”

Currently making do with a 20″ A. medium ride, and an 18″ (Canadian) K., and a pair of 14″ New Beat hi-hats, Christina obviously hears something in those old cymbals, and seems mildly put off by today’s heavier modern cymbals. “There’s something wrong with most of the cymbals I see on the shelves these days. They’re either too dark or too light; too much buildup; too slow or too fast; not enough ping. The main thing is I can’t get the sound out of each section of the cymbal that I like. You ought to be able to get an articulate, even sound all around the cymbal; something distinctive from the bell; a sort of clear half-crash in the middle; and a nice controlled explosion that doesn’t swamp the sound when you come back in the ride.

“I may be wrong,” he continues, “but it seems like the quality of the brass, or how they’re processing it, or the way they mix it, or the way they finish the cymbal seems different. The new cymbals don’t sound like the same instruments that they were 10, 15, 20 years ago. Something’s wrong. I’ve heard some Paistes that I like…but you get a one-formula cymbal and they make them all sound the same. Who wants to sound like everyone else?” he laughs. “Oh, this is the Formula such and such, this is the most popular one, the one so and so is using.’ Big deal. I don’t want to be popular. I want to sound like what I like.”

How Christina sounds is partly a product of his lack of formal training (coupled to an abundance of practical experience and the encouragement of musical friends like guitarist Duke Robillard). “One of the reasons why I never developed a habit of practicing, was because I felt like everybody was being bugged by it. So they threw my drums in the basement, and what I used my drums for half the time was basic frustration-vent go down and take a two hour drum solo and block out everything. Then, around the time I was 14, the desire went away, and I stopped playing drums for a couple of years. Then Duke came along and said, ’Hey, man, I’m starting this band, and I want you to play drums.’ And I said, ’Nah, I can’t play the drums, you guys are too good…’

But Christina got talked into it, which is how he ended up playing the hardcore Texas r&b of Roomful Of Blues and the driving Western swing of Asleep At The Wheel. He soon began incorporating his many influences into a southpaw’s style. “I was into everyone from Baby Dodds to Sid Catlett; from Elgie Edmonds to S.P. Leary. And Mr. Al Jackson, I really took a hankering to him and all of the New Orleans drummers, like Earl Palmer they had such a great feel. I’m pretty much a product of that Louisiana sound. I got turned on to those rhythms again when I had a chance to go to New Orleans with the T-Birds. Before I went there I knew what it was they were playing, but when I went down there and saw it I knew why they were playing it all the styles from Zydeco to the jazz. It all has that little extra hip shank in it; that street dancing, the grease, and that second line call and response. I got really turned on to the whole attitude of those rhythms when I got to see them up close, in the context of the community.”

As for being a lefty playing a righty’s kit, Christina pleads ignorance. “I didn’t realize it until I was 17 years old, that I played backwards and upside down,” he laughs. “I guess what happened is that people started telling me that, and I hadn’t noticed. When I first started seeing drummers, most of them were right-handed and set up that way. And I was looking at them, so when I got my first set of drums, I set them up to feel comfortable, without anyone to tell me how. It’s weird. I throw with my right hand, but I write with my left. So I don’t know if that has anything to do with it, but that’s how I feel comfortable.

“The thing is, there are patterns that right-handed drummers play real easy and natural that I have to think about, and vice-versa. But there are a lot of things that come easier to me than for a righty; just getting around the kit on certain things. It’s like the left side of my kit is pretty much played with the left side of my body, and the right side with my right. So I might tend to accent like a mirror image of the way someone else would.”

Moving around from Roomful to California, Kentucky and Ann Arbor, Christina increased his playing experiences even as the entire music scene was coming under the spell of the new popular rock of the mid-to-late ’60s. “How’d I take to rock?” Christina asks rhetorically. “Well, I went to Shea Stadium to see the Beatles, and that sort of turned me off to rock concerts forever; pressed up against a chain-link fence, with 40,000 screaming girls crushing against you, and no sound to speak of, it was terrible. But I got caught up for a short period of time, certainly. You’ve got to respect the Beatles, of course. And the Stones and the Byrds. It was a weird period, because here I was presented with all the popular rock of the day, like Traffic, and I’d been listening to all this blues. Still, King Crimson and Jimi Hendrix got to me for a while, and I guess I was captivated by it all for a year or two. But I was pretty wide open to anything back then.

“But the stuff that stuck with me after the infatuation passed was like, Carl Perkins. I mean, I played it all, and once I realized where all of this stuff was coming from, I began checking out the original roots of everything that was breaking: Louisiana, South Texas, Memphis, Chicago, that’s what originally drew me to music, and that’s what kept me in it.”

But after the Ann Arbor music scene more or less dried up, Christina found himself discouraged by the day-to-day rigors of the music business, and after 10 years of playing, he decided to hang it up for a while. “I’d gone up to Nova Scotia to visit a friend, and I found a chunk of land and a house up there real cheap, and I just moved up there. I was getting real tired of club owners screwing me around, so I didn’t want anything to do with it for a while. It’s actually Duke Robillard’s fault that I left Nova Scotia and began playing again, but I was up there for a good four years, and in that time I started playing with the T-Birds. A friend of mine, John Nicholas, who used to play with Asleep At The Wheel, was the one that put us together.

“You see, the T-Birds came up to New England and they brought along a drummer who had never been out of Texas before… I guess he was like 45 or so, and he just didn’t know how to handle it when they hit Boston. And they woke up one morning and he was gone, no note or nothing, right in the middle of a long tour. So my friend John heard that they were looking for a drummer, and told them there was this guy who lived up in Canada. And they called me up. Well, they didn’t call me up. I didn’t have a phone, so they called the Canadian Mounties, and had them deliver the message that ’The Fabulous Thunderbirds need you to play drums next week in London, Ontario.’” Christina breaks up at the memory. “So then, I had to hitchhike from Nova Scotia to London, just south of Toronto, about 1500 miles, and it took me a couple of days, because I didn’t think I’d have that much trouble getting rides. All I brought along were my sticks and my snare, because when their drummer split he just left the drums, so I used his old set of Slingerlands, which had been through a pretty thorough beating.

“All I knew about the T-Birds, because I’d never heard them you understand, was that my friend John thought that they played my kind of music and that we’d work out well together. And from the first note it was like, ’I’ve found my brothers!’ Me and Jimmy just kept looking at each other, surprising the hell out of one another. He’d respond perfectly to some idea I threw out at him, and it was fantastic; it was just the way I’d always been thinking about this music. So I’d play with them on the road in New England anytime they were up in my neck of the woods, and it just grew from there.

“The role of the drummer in this music is just about as basic as you can get. Forget the flash and the trash and just get down to drivin’ the band from the bottom, kick ’em in the butt. I know that the simpler I play, the more straight-ahead, the better the band plays, especially the guitar player. With harp players… well, harp players get a drive happening out of accenting the groove; there’s a certain kind of push that harp players need from me. When they go to accent things, it really has to have that push. That’s where I would use accents more, whereas guitar players like Jimmy, I don’t know about most guitar players, but what Jimmy likes is something to ride on. He has a sense of time that’s so strong, he doesn’t need me to remind him of the beat, just to make it bigger and prettier. The great thing about this band is that we all have a similar time sense; we don’t think about the time, it’s just a feel that we share. Keith and I are so tight I don’t even have to listen to him. he’s always there. It’s really a shock to me on the infrequent occasions when he does stumble a bit, which is like, never. The way these cats play is so laid-back, unpremeditated and spontaneous. Everybody is playing at it, and not playing. Down there in Texas, most of them grew up with their instruments in their hands, listening to the same sources, some really raw shit happening musically, something that you can’t shake. It’s a thing that’s indigenous to Southwest Texas and Louisiana, that real ancient rhythm & blues.

“That’s why we can play as a unit the way we do. When you don’t have to think about the music and the time, it’s so easy, because you don’t have to be considering, ’Well, how should I play this fill, or where should I put this accent?’ Then you’re playing music, and that’s when it starts to happen. That’s why it’s difficult in the studio, because you start planning. ’I’m going to do this here, and put that there.’ You can’t play music while you’re thinking about arithmetic. You’ve just got to let it breathe and come out of the sticks.”

All of which brings us beyond a discussion of musical attitudes and into a bit of background on the different kits and setups Christina has used over the years; the peculiar challenges of playing live or in the studio; and coping with musicians who possess differing styles and time feels.

“I always loved the sound of those old Slingerland Radio Kings,” Christina enthuses. “They have an incredibly fat, warm sound. I’ve had a number of sets of them over the years, and that’s what I’ve got now at home in my little practice room. They’re my favorites. The only drums I’ve ever found that I liked as much were an old set of Fibes… which is an interesting story. I was just home at my folks last week, and my younger brother, who plays drums too, called me up to tell me he thinks he found my set of drums. You see, I had this set of Fibes stolen when I came down from Nova Scotia to play with Scott Hamilton, Chris Flory and Mike Ashton (who play with the Widespread Depression Orchestra); we have this little four-piece bebop band called the Whiz Kids. And I’d gone down to Boston, stayed over at a friend’s house and had my drums in the back of the car, I had a gig with these guys that night in Providence. So that day, my wife, who trains horses, had a horse running at Suffolk Downs. I went to see her horse and didn’t even bet on the thing, and it came in at like 30 to 1. So I came back to my car to go to the gig, all bummed out because I didn’t bet on this horse, and when I opened the trunk the Fibes are gone, and those cymbals I was telling you about, too,” he added with an audible sigh.

“And these Fibes were a really neat set of drums, like one of the original sets when the guy started making ’em, just before he got bought out by Martin; I’d really fallen in love with those things when I heard Mose Allison’s drummer playing a set. I liked the way those drums were real punchy and crisp, a little too crisp, in fact, for me. So what I did was put calfskin heads on ’em, and it was neat, because you got a warm sound but it was still punchy. So these were stolen like nine years ago, just as I was getting used to them, and my brother’d been looking for the same type of drums, and he found a set of Fibes and they were those drums, believe it or not. So right now they’re owned by my sister-in-law’s cousin’s son, with all these thrashing marks on ’em so I know they’re the ones. Pretty wild, huh? I’m thinking of going over and asking him if I can buy them back.

“But what I’m doing now is making a set of drums. I sent this guy MacSweeney at Eames up in Boston my specs for what I want, and I understand he builds great shells; so he’ll send them to me, and I’m just going to paint them myself. I’ve got a good friend in Austin who’s a guitar painter, and he’s teaching me how to use the gun and all, and I’m going to put custom hardware on it, the very best I can find.

“I’m in a different situation now, where I’m not playing acoustic anymore; I’m playing amplified drums, and I hate to admit it, but I have to mike my drums, they have to be miked. I don’t hear them the same way; the sound isn’t reproduced the same way for the audience, so it’s like I’m starting over again. I mean, I had my set of Radio Kings that I found in a garbage can right next door to my house that I refinished, a great set of drums, real meaty sounding and warm with these mahogany shells, but I just took them off the road because they were taking a beating and it wasn’t working out.”

“Weren’t they projecting,” I wondered?

“Well, it’s not a matter of projecting,” he explained.

“You mean that all of these wonderful subtleties of tone which you were used to hearing just don’t carry over live, because the frequencies cancel out?”

“That’s the deal,” Christina concluded. “I have to make a compromise between what my sound is on stage, and what the sound man has to work with. So I have to work with him to some extent; I mean, I tell him what I want and what I’m pre pared to do. Like I’m not going to take the bottom heads off and I’m not going to make the drums feel like I’m banging on a paper bag. I want to be able to get something close to the sound I’m used to. We have our own sound man on tour, and he’s real receptive and understanding, so he’s pretty much got it together. But he’s up against it as well, from playing places that seat 500 to an 18,000-seat hall. Those subtleties just don’t come through, so the name of the game is punch, which is basically the way I play with the T-Birds, probably with anybody I’d like to play with. It’s the kind of stuff I’ve always played, you know, hard blues; straightforward heavy-backbeat kind of stuff.

“The drums are all Premier that I’m using now. The snare drum is like an 8 1/2″ x 14″, I think. I just asked them to send me the biggest, meatiest snare drum they could, and this is what they came up with. It’s what you would call a fairly loose, open-sounding snare drum.”

Sure. Unlike those snare drums that go “thwack,” but choke up right next to the hoop.

“Yeah, I hate that too. It’s like the drum’s saying ’I ain’t supposed to do nothin’; I’m right out on the outer limits.’ I like a snare to sound like a snare. I’m still working with my soundman Dave to get the sound that we both like. I like the snare to have some depth, some shot and some pop. The other drums I’m using are a 14 x 24 bass drum, and a 9 x 13 rack tom, and a 16 x 16 floor tom. With the new kit I’m having made it’s practically the same thing, except the kick drum will be two inches deeper, so it’ll be 16 x 24, and the rack tom will be 10 x 14. I’m hoping that the extra depth on the bass drum will make it more like that donut when the punch comes through there. It’ll be interesting to see how the drums will react with those thick wooden shells. I suspect that with the birch shells it’ll project better, yet still keep the sound warm; it may be a mistake but I have to try it out, because I think that the way we have the drums miked now, we can get the punch out of them, but I still want the warmth, and that’s so easy to lose.”

The whole art of amplified drums, is in miking the kit so as to bring out the fundamental. But how does one bring out the center of the stroke without sacrificing all of the tone and resonance one is used to hearing in an unmiked acoustic kit?

“Well, that’s a challenge. All I really want out of my sound man is to help me project the sound I like to hear, and I’m willing to stretch a little. I mean, I never, ever used to use Pinstripe heads; I was always just a straight Ambassador or calfskin man, all the way. But that was only a minor concession for me, just to get rid of some of the ring, and Pinstripes are a good compromise because they don’t impair my technique, and they have a nice, warm, fat sound. You see, I always like to play drums with a lot of ring, and acoustically it doesn’t make much difference, but in miking it, that just amplifies the overtones and the ring more than it does the fundamental sound of the drum. So I had to compensate for that. I’m always learning.

“Through using the Pinstripes, I’ve been able to bring out more of the sound of the drum. I just tune the drums up so that they sound in tune with themselves; not up to pitch, even though it ends up as one; and I suppose over the years I’ve been hearing a particular interval that I like. Mainly, though, I just tune to get the feel of the drum right, and to bring out its individual voice. It’s funny, I’ve heard people play on my drums, and it’s just not the same thing. The way I play, I can’t sit in the house and listen to someone play my drums, because they just don’t sound the way I play them. It has something to do with my technique, I guess.”

As Christina and Dave didn’t bring their own mic’s out for the most recent T-Bird tour, each situation has presented a unique opportunity for trial and error. “Right now we’re just using whatever the clubs have,” Christina shrugs. “Generally we like Sennheisers and Shures. Shures are particularly good for the snare, like the Shure SM57 or 58. Sennheiser 42/s are good, too, for toms and stuff; and we decided that we really liked the AKG D12A for the bass drum. Every gig we try out different mic’s, always experimenting to figure out which mic’s hear what, and we narrow it down to what I like to get out of the drums, and what the mic’s are capable of. So pretty soon we’ll find the mix we like instead of just going with the house mic’s.”

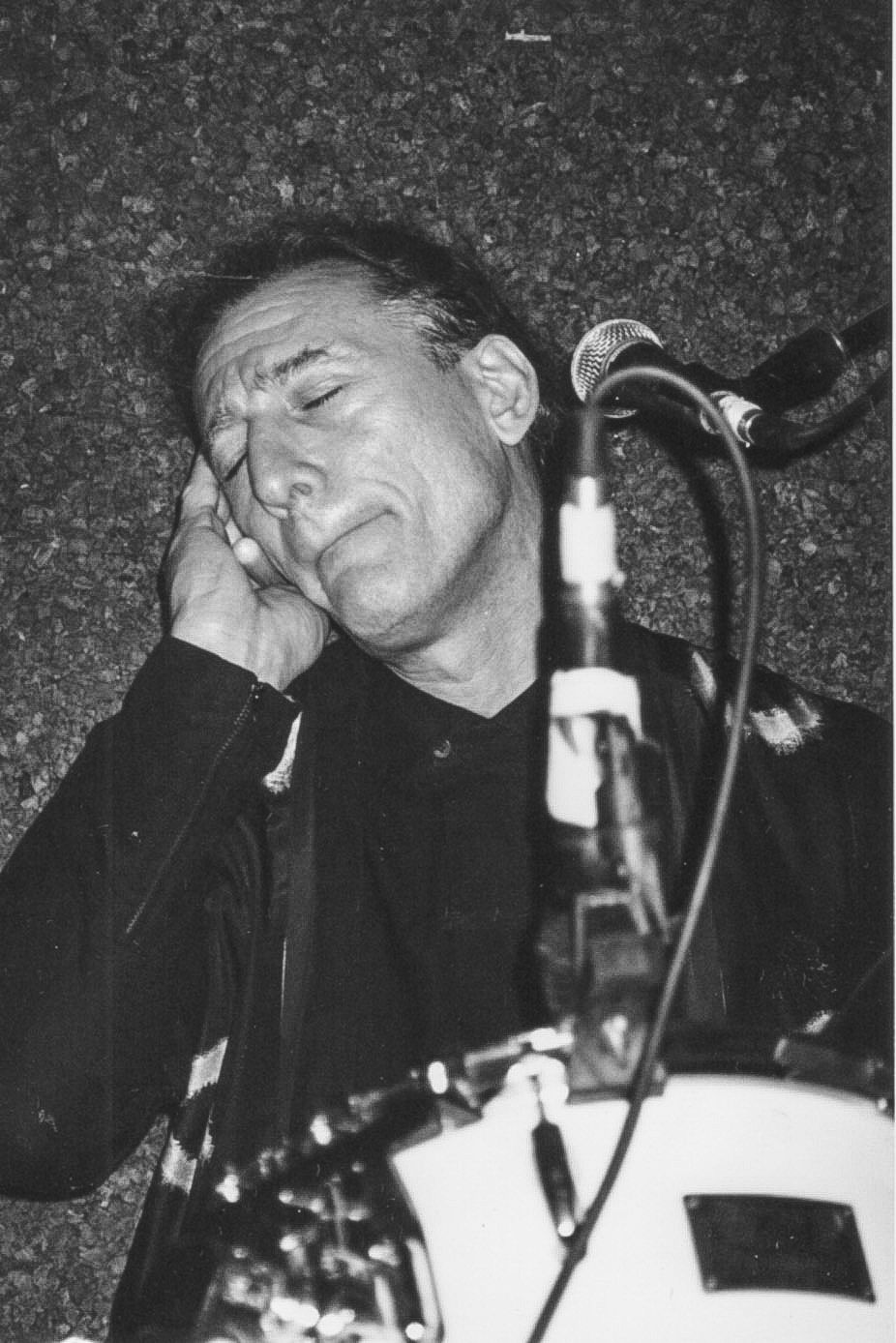

Fran’s road manager interrupts our ruminations with a reminder that soundcheck is at 5:00, and the guys want to get back to the hotel. We walk across the street to the Bottom Line, where we find Jimmy Vaughn struggling to locate a noise source in his signal chain. The sound of his Fender Twin Reverb, Stratocaster and Leslie cabinet is wet and reverberant; his ringing blues phrases hang in the air like a curtain of tears. I see what Christina means about the Thunderbirds’ time sense. They are swinging without a drummer, and apparently they don’t require their drummer to play like a fashionable metronome, digging coal out of his snare drum. Christina begins orchestrating the band’s groove in an offhand but firm manner, feeling free to signify and cajole, yet never getting in the way. He throws out a few smoke signals to me, as well, commenting musically on some of the styles and postures we’d dis pull up a few plums from his other bags, including swing figurations and some stick-juggling flash. “Stop showing off,” says his soundman, teasing him dryly.

I told Fran that I never suspected he had all this show biz stuff together. “Yeah, that’s fun,” he chuckled. “Sonny Payne with Count Basie inspired me to try that; an unbelievable drummer I mean, I just fool around with it. When Basie would be doing these flag waving, uptempo things, Sonny’s one hand would be carrying the beat, and he’d flip this stick behind his back without even looking, catch it, and bring it in on the snare right on the beat, after falling like 30 feet in the air. Man, he had more rhythm in his baby finger than I have in my whole body.

“I guess I picked up on all that big band swing stuff through my experiences with Roomful. Asleep At The Wheel was more Texas/western swing, but that’s a similar groove. I guess my jazz licks come from playing with my friends in the Whiz Kids. I don’t even know where I picked all that up.”

“Well, when you’re not thinking about what you’re doing,” I quipped, “what do you think might be the difference in posture between what you’re doing when playing the low-down dirty beat, and the swing beat?”

“The low-down dirty beat I have no problem with,” he asserts, “because that’s just they way I hear things. I never even knew there was a difference until I started playing with Asleep At The Wheel. Then I realized that there was a difference between playing Charlie Christian/Count Basie swing and country/western swing, which was just a white version, what I call cracker swing.

“You don’t even realize what the difference is until you look at it real close. To me, the beat is like a foot long, and for the kind of thing I usually play, backbeat stuff, that’s just what it is; you play the tail end of that note, and that’s what I think gives it the fatness and the depth and stuff. Now when I started playing country/western swing, it’s more like at the beginning of the top-end of the beat. Do you follow what I’m talking about?”

“Well, I usually think of jazz as being a horizontal beat,” I said, “rock as a vertical beat, and funk as a diagonal beat. I think what you’re saying has to do with treatment and interpretation of the beat; how you syncopate on or off the beat.”

Christina continued: “It’s like if you took the same song, and had different cats play it, you’d hear a different inflection. Like in cracker swing, if you put a metronome on it, it would probably be right on time, but if you took the same song with some black swing players, it would still be right on time, but the metronome wouldn’t mean so much. It’s like you wait until the last possible second to hit the drum.

“That came up during our collaboration with Carlos Santana on his latest solo album; he wanted the T-Birds to be on the album. People forget, but his original band was the Santana Blues Band. It’s funny, because when we started working with Carlos, coming from the Latin side of rhythm, their time is more on the front of the beat, right on top of the ’one,’ really pushing it; and, well, I play the back of the beat, so far back you almost fall off, but not quite. And when we got together it wasn’t clicking; we were playing the same thing, and it was all in time, but it was like an outer-space docking procedure to get it together.

“We were doing blues tunes, only with Latin percussionists. We had Santana’s fantastic Cuban-wall-of-rhythm, and we came up with some new kind of fusion music. I don’t ever think I’ve heard the blues sound that way, once we came up with a compromise on how to accent the ’one’ so it didn’t just pull apart. We’ve got the most unique version of Bo Diddley’s ’Who Do You Love’ that you’ll ever hear, only I didn’t do the tom-tom thing, just a straight backbeat with the Cuban wall puttin’ their Latin flavor to it, and it was really a gas. That’s like the difference between the cracker swing and the Basie swing it’s a matter of where you put the feel. The cracker thing is a little more on the beat, while the Basie thing is a little bit more of a laid back, up-from-the-bottom kind of push. You really lay back and everybody gets a chance to feel the space in between the notes and to do what they want with the time. It makes it real soulful.”

Which is as good a way as any to sum up Fran Christina’s style of drumming, a triumph of gut feeling over empty chops. Some of today’s hyper-clean jock drummers (and engineers) might miss the point of his sound, inadvertently hear it as sloppy, and try and suggest that he, you know, “Clean up a bit man; muffle them drums; get into that practiced, precision sound.” Which is not to suggest that Fran Christina isn’t takin’ care of biz. No. But Fran Christina is a feel drummer; he knows the language, the vocabulary of the blues, and he ain’t interested in being MOD-Dern or trendy.

“I have the type of drumsets and sound that most engineers cringe at in the studio. They start coming at me with pillows and gaffer’s tape, but I just tell ’em where I’m at when I get there. And then they say, ’Well, what do you want to sound like?’ And I tell ’em, ’Look, just make me sound like Al Jackson.’ They have a hard time doing that nowadays, but you know, those articles you had in Modern Drummer on microphones were really helpful to me the last time we went into the studio to do T-Bird Rhythm. That gave me some good in put to go by when we were working on the drum sound.

“I’ll tell you,” he confides, “I love playing with the T-Birds. I get to play a lot of fills and a lot of energy, but I honestly don’t know what they are, what they’re going to be, or what it is I’m doing or what you’d call it. I try not to think about it I just try to let go and move with the music and I usually don’t have any problems. As far as practice goes, I’ve never been a rudimentary-reading type. Not at all. You know, I make my little attempts from time to time, to learn to read. But invariably I get bored and feel like playing. I’m a little old for that now, but I’ve come this far without it, so what the hell. Besides, I’ve had real on-the-job training in playing this music since I was 15. Practice, and I’m not just copping an attitude or anything, has never been convenient. Drummers know what I’m talking about. It’s really hard to find a space to practice where people aren’t bugged by the sound, and hey, I can sympathize with them. I mean, who the hell wants to listen to somebody practice their chops all day? It’s a drag, and if I had to listen to it, I’d go nuts, too even if it was Art Blakey. Just for myself, I love my drums, and I love my wife, and I figured I could keep both if I didn’t practice.”

The Scene Is Gone But Not Forgotten

The Evolution of Austin's White Blues

FRI., AUG. 9, 1996

by Margaret Moser

"Well, I used to go to Antone's every weekend but all the good bands are gone."

That sweeping statement came recently from a longtime Antone's patron. He wasn't being mean-spirited, but rather was reflecting an unspoken sentiment among a number of Antone's aficionados -- that the white blues scene that gave Austin its reputation as a blues town is gone.

That might not have been obvious during its 21st anniversary celebration last month, when Antone's stayed full nearly every night. One evening, Susan Antone hid out in her office with Derek O'Brien, Speedy Sparks, and Lou Ann Barton while Angela Strehli was onstage belting many of the same songs she'd sung 20 years before. The subject was the scene that had nurtured them all and what had changed. "I don't know if anything's different -- I'm still the same." Barton took a long drag off her cigarette. "But the audiences -- they don't come out like they used to, do they?" I asked her. Barton shook her head, resembling tragic Thirties actress Louise Brooks with her cap of short hair and dark, velvety eyes. "No," she exhaled, the smoke flowed from her cigarette and curled above her like a question mark. "They don't."

Austin is known worldwide as a blues town, but does it still deserve the title? Yes and no. The white blues scene of the Seventies that spawned that rep is gone. After playing more than a quarter of a century, lifestyle blues have set in for many of the players, singers, and musicians. Some of them have decided to pursue individual interests and careers, producing records and doing session work, downshifting away from performances and years of touring. In other cases, drugs and alcohol have taken their inevitable toll. It's a lot easier to play the blues all night when you're 22 and life is but a dream than when you're 47 and pay the mortgage by working a day job. What's taken the place of that scene is no less vital -- but it is, in every way imaginable, different.

1973-78:

Get High, Everybody, Get High

White girls like me didn't grow up hanging out in juke joints. I learned the blues from the Rolling Stones, Cream, and Janis Joplin, from listening to odd Top 40 hits like Slim Harpo's "Scratch My Back" and seeing Otis Redding in Monterey Pop. Monterey Pop made it hip for rock festivals to include blues players and jazzmen of all ages and styles, so I got to see Albert King, Jimmy Witherspoon, War. I had also heard blues through a series of black maids my family had. Faye used to crank that radio up in our suburban Houston home and whoop and holler blues along with it. In New Orleans, Anna Mae didn't sing but she did keep the radio on a station that constantly played the local bands -- Bobby Marchand, the Dixie Cups, Aaron Neville, Ernie K-Doe, Irma Thomas, Fats Domino, Huey "Piano" Smith. I was raised in a privileged background that wasn't devoid of troubles, but it certainly wasn't the blues. When you're white, blues is almost always an acquired, if still instinctual, state of mind.

Mostly, I learned the blues during my late teens in Austin's dives of the early Seventies, from Jimmie Vaughan and Doyle Bramhall in Storm, Paul Ray in the Cobras, W.C. Clark and Angela Strehli in Southern Feeling, and Stevie Vaughan and Keith Ferguson in the Nightcrawlers. I attended all the proper institutions of higher learning, all puns intended, thank you: the One Knite, Flight 505, the Black Queen, the Gig, the Lamplight, the Sit'n'Bull, the South Door, the Back Room, and the Buffalo Gap (which became Raul's and is currently Showdown). Often, I got to hear some of the famous ones at the Ritz and Soap Creek, who would bring in Son Seals, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, the Meters, Jimmy "Fast Fingers" Dawkins, Koko Taylor, Bukka White, Lightnin' Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, and other bluesmen.

The young blues players, many of whom had migrated here from Dallas, also patronized some of Austin's black blues clubs like the old Victory Grill, a converted gas station called Alexander's in what was then rural Sunset Valley, and Ernie's Chicken Shack on Webberville Road. At La Cucaracha on the Eastside, where the newly constructed interstate had yet to culturally divide the city, a pre-PC nirvana was taking place: White boys were playing black music in a Mexican restaurant. On a national level, music was in stultifying limbo; no wonder the volcanic blues erupting from greasy dives locally seemed infinitely more exciting.

Even so, the hometown audiences didn't exactly get it. Austin was, after all, the center of the universe for progressive country, redneck rock, and cosmic cowboys. National attention was heaped upon Austin for this brave new sound and its accompanying lifestyle. At night, sawdust was kicked up on dancefloors from Soap Creek, the Alliance Wagonyard, the Broken Spoke, and the Split Rail all the way to Luckenbach. This outlaw music was potent because it reached into Texas's country music roots and a staid audience rarely phased by trends. If blues wanted to survive in this foreboding atmosphere, it needed all the strength it could get. But that was okay: Blues by nature is music about survival.

ge quonset hut that had once been a National Guard Armory at the corner of Barton Springs Road and South First Street, the Armadillo World Headquarters was definitely cosmic cowboy central -- but it also booked blues. It brought in Texas legends like Mance Lipscomb and blues-rockers like Freddie King; the Armadillo also brought in gospel with the Mighty Clouds of Joy, jazz with Gil Scott-Heron, and soul with Al Green. But the sentiment among the blues musicians was that the Armadillo didn't support local blues; possibly the Armadillo felt there was no audience. Paul Ray remembers that, "sometimes the Armadillo would put Storm, Southern Feeling, and the Nightcrawlers on a bill but the only people to show up were the same group of friends and girlfriends."

The feeling of rejection remained long after the music hall shut its doors. "To tell you the truth, when the Armadillo finally closed [Dec. 31, 1980], we thought it was the best thing in the world. That's when we started getting the good gigs," Jimmie Vaughan confessed to me in 1995, 15 years after Austin's answer to the Fillmore shut its doors. Still, the Armadillo represented Austin's easy-goin', dope-smokin', beer-drinkin' lifestyle that was conducive to the pursuit of blues. At the very least, the Armadillo gave progressive country an address, a home base. Maybe it was time for the blues to get one as well.

If luck is defined as preparedness meeting opportunity, those two elements bumped head-on at the corner of Sixth and Brazos in 1975. After scrounging around in cramped dives for years, the opening of Antone's nightclub was a godsend to the local blues musicians, even if Angela Strehli was more likely seen there mopping floors than singing. A refugee from Port Arthur, owner Clifford Antone was simply interested in seeing all the blues he could, and he figured opening a club was the best way to do it. Because it was more economical for him to bring in out-of-town musicians and book them Tuesday through Saturday at the club, names like Sunnyland Slim, Albert King, and Jimmy Reed would hunker down in Austin for a week or so, usually playing to respectable weekend audiences and lighter crowds on weeknights.

The newly formed Fabulous Thunderbirds began playing there regularly. A holdover band from the days of the One Knite, Paul Ray & the Cobras -- now sporting Stevie on lead guitar -- could pack Soap Creek every Tuesday and still command a weekend crowd at Antone's. House players like Bill Campbell, Derek O'Brien, and Denny Freeman honed their chops behind Eddie Taylor and Albert Collins, and the scene soon became strong enough to begin evolving seriously. By 1976, Stevie had left the Cobras and formed Triple Threat Revue with Lou Ann Barton, W.C. Clark, Mike Kindred, and Freddie Walden -- which begat Double Trouble in mid-1978. The Cobras, the Thunderbirds, and Triple Threat/Double Trouble quickly emerged as the holy trinity of bands at the temple of the blues.

Band members and audiences even dressed as if they were going to church. A kind of "anti-hippie" style developed -- part Fifties soul, part Texas pachuco. Long hair was shorn and slicked back, beards were clipped into debonair mustaches and imperials, and jeans and T-shirts were shucked in favor of ostrich boots and vintage shirts. Lou Ann Barton set trends with her wardrobe of torchy cocktail dresses and dangerously high heels. On a good weekend night, Antone's long bar would be lined with cocaine cowboys holding turquoise-and-silver hands with crimson-mouthed young women in whispery taffeta.

White blues in Austin was getting as good as it would get during those years, partly because of the musicians and partly because of Antone's. When a Willie Dixon or Barbara Lynn or Bobby Blue Bland was onstage at Antone's, the smoky ambience of the blues was as real as it had ever been. If a bluesman was still alive and touring, Clifford Antone probably booked him. With its ready availability of blues masters, Antone's gave local blues an identity, a matrix, a home. And the players recognized the opportunities, never missing a chance to talk to, hang out around, or play with the bluesmen. Those Blue Mondays never sounded as good as they did immediately following a week's residency by one of the legends.

The house was a-rockin', but it wasn't getting much respect. Muddy Waters may have smiled approvingly upon the Antone's musicians, but Austin's reputation still had a big ol' cosmic cowboy hat on its head. When The Austin Sun's 1976 Music Poll recognized Angela Strehli in its cosmic cowgirl-dominated Top Ten Female Vocalists, it prompted Paul Ray to write in and note how remarkable it was that Sun readers acknowledged Strehli, a performer "without the Armadillo seal of approval."

If this seething little hotbed of activity was looking for peer reinforcement it didn't get from the Armadillo, it got it when Bob Dylan's all-star Rolling Thunder Revue came to town and parked itself across the street at the Driskill Hotel. For nearly a week in mid-May of 1976, you could walk into Antone's and while there might not be 40 people in the house, the head count probably included Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Roger McGuinn, Bob Neuwirth, Kinky Friedman, Joan Baez, T-Bone Burnett, and Steve Miller. James Cotton was playing the weekend and the Thunderbirds were also booked as rock's royalty wandered on and offstage with various bands. Luck = preparedness + opportunity. Antone's became the place for touring stars to visit, as Maria Muldaur, the Pretty Things, Bonnie Raitt, Elvis Costello and others trekked there in its early years. It didn't hurt that the national music press noticed, either.

At Antone's, something was happening, and the image of the sassy Lou Ann Barton perched on the knee of the mighty God of Blues said it all.

Visiting rock royalty was, however, expected to honor its blues forefathers properly. When Boz Scaggs and entourage swept through Antone's cramped backstage and demanded an audience with Bobby Blue Bland, Bland's bodyguards didn't know who Scaggs was. Scaggs was sort of the Stevie Ray Vaughan of his day, a suburban Dallas white boy playing blues who caught the popular ear. Scaggs was critically liked and achieving success at the time, and did not take kindly to the snub. When he tried to muscle his way past the door to see Bland, he was cold-cocked by a punch that sent him out the door onto his back on the sidewalk. The photo ended up in Rolling Stone.

Ultimately, it was the legends themselves who gave credibility to the white kids, as in Muddy Waters inviting Jimmie Vaughan, Kim Wilson and Angela Strehli up to play with him or Albert King stopped cold by a 23-year-old Stevie Vaughan. But the enduring image was captured when Lou Ann Barton sat on Waters' knee and posed for a photograph that also landed in Rolling Stone. Over at The Rome Inn, at 29th and Rio Grande, the Fabulous Thunderbirds' Blue Monday gigs were providing another outlet for the electrified scene. Those gigs especially picked up steam when Antone's was forced to move from its Sixth Street location to a forbidding location on Anderson Lane. Clubs like After Ours, Soap Creek, and often Steamboat also juggled the T-Birds with the Cobras and Double Trouble, and week after week it was still paying off in increasing crowds.

Suddenly, it seemed every night was New Year's Eve, and the most uneventful weeknight might turn magical, throbbing with raw, homegrown blues. On an otherwise uneventful Sixth Street, something was happening at Antone's, and the image of the sassy Fort Worth shouter who'd cut her teeth playing Jacksboro Highway juke joints perched on the knee of the mighty God of Blues seemed to say it all.

1978-1990:

Dreams Come True

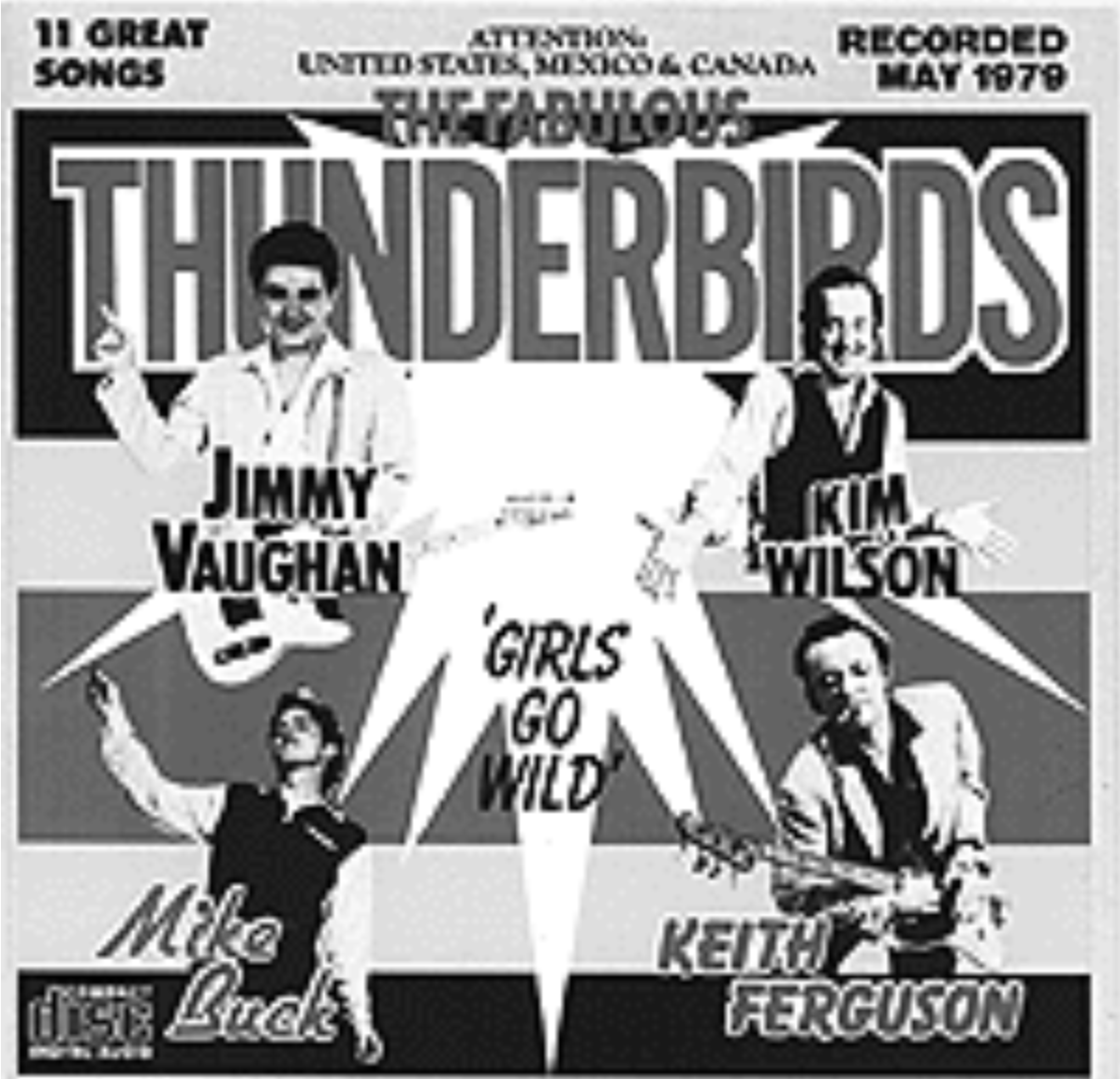

If the image of Lou Ann on Muddy's knee was a symbol of Austin's emergence as a player in the blues game, it still had no product to show for its blues talents by 1978. All the rock luminaries in the world could pay homage, but not one local band had a record, single, or even a tape available to back up the claims of stellar talent. While recording a CD seems effortless today, even recording for a cassette tape then was much more complicated. The Cobras had recorded a single, "Texas Clover," while Stevie was with them, but that was about it on the horizon. Still, the thumbs-up Muddy Waters and other blues legends had given the Thunderbirds paid off; the T-Birds were signed that year and recorded their first album for the Takoma label in May of 1979.

For my money, The Fabulous Thunderbirds' first album is the best white blues recording to ever come out of Austin. Often called Girls Go Wild but truly eponymous, it's raw and uneven and unself-conscious in its exuberant celebration of the music Jimmie Vaughan, Kim Wilson, Keith Ferguson, and Mike Buck seemed born to play. It was low-down and dirty, much more suggestive of a too-close slow dance than wild rock & roll abandon. In rapid succession, the Thunderbirds issued three equally good follow-up albums --What's The Word? in 1980; Butt Rockin' in 1981; and T-Bird Rhythmin 1982 -- that hit like a grand slam and brought it home every time.

Blues was still a hard sell elsewhere, however, even if the Thunderbirds were beginning to draw huge audiences at home and word of mouth was good on the road. As cool and distinct as the Thunderbirds were, they looked like old guys, an even tougher sell to kids. On the home front, though, the Thunderbirds' popularity could be tracked in the Chronicle music polls, where they were the first Band of the Year, a category they would dominate for several years. The Thunderbirds were bad-ass, but critical praise and hometown-hero status still weren't selling records for them.

By the time T-Bird Rhythm was released in 1982, Stevie had noisily begun his climb to stardom by turning down David Bowie's offer to tour as his guitarist in favor of sticking with Double Trouble, signing with Epic/CBS, and teaming with producer John Hammond with plans for a first album in hand. Texas Flood was an appropriate name for the first record from the guitarist now billed as Stevie Ray Vaughan, for when it washed across the airwaves, a new face of the blues was born.

That's all history now, how Stevie and Double Trouble leapfrogged up the ladder from Texas Flood to Couldn't Stand the Weather in 1984 and Soul to Soul in 1985. How the Thunderbirds finally scored big in 1986 with "Tuff Enuff," a hit so catchy it still gets tacked onto soundtracks ten years later. How Stevie was starting to hit the skids with drinking and drugs, and didn't put out another studio album until he cleaned up and released In Step in 1989. How the Thunderbirds began to falter as their killer hit had little in common with their blistering blues repertoire. The record sales didn't go through the roof for either Double Trouble or the Thunderbirds by the late Eighties, but one thing was absolutely for sure: If you asked the average musically astute person what Austin music sounded like, the answer would be "blues."

That seemed logical. Behind the relative success of the Stevie and the T-Birds, Antone's established its own blues label as CD technology made local releases much more feasible. One longtime project was realized when Marcia Ball, Lou Ann Barton, and Angela Strehli recorded Dreams Come True for the label, arguably one of its best efforts. Chronicle music polls continued to be dominated by Stevie, Double Trouble, and the Thunderbirds, while Lou Ann and Angela had played tug of war for Best Female Vocalist since year one. Toward the end of the Eighties, you could almost set the calendar by the Thunderbirds' traditional New Year's Eve show, Riverfest in May when they drew thousands, and a couple of local shows in between. Stevie's homecoming shows bordered on awe-inspiring displays of jingoism. For a few minutes, dreams really had come true.

If a time and place can be named when those dreams were shattered, it is surely August 27, 1990, when Stevie Ray Vaughan's helicopter slammed into a mountainside in Alpine Valley, Wisconsin. Stevie had been Everyman with a Stratocaster, the not-so-pretty boy, the younger brother that tried harder. Stevie had given white blues individuality and personality. For many, he was the face of blues, the success story, even if his brother's band had charted more hits. Stevie was the perfect symbol of success after hard work, always acknowledging the bluesmen he'd learned from at Antone's: Muddy, Albert, Buddy Guy, Hubert Sumlin, B.B. King, etc. And in one blinding flash of human error, it was gone.

1990 to Present:

Change It

The tragic event that left a pall over 1990 also cloaked 1991, the year that Seventies blues scene quietly expired.

Stevie Ray Vaughan was dead and Double Trouble was over. Angela Strehli had followed her heart to the Bay Area, and eventually married longtime love Bob Brown. Paul Ray had retired from singing in the Eighties before the Cobras broke up, but both were off the scene by the Nineties. Lou Ann Barton doesn't have a record deal, and in recent years has been almost invisible in a scene she once ruled, though she's undisputably the Queen of Austin Blues. The Fabulous Thunderbirds evolved into little more than Kim Wilson's back-up band after Jimmie Vaughan left (and should maybe be billed now as Kim Wilson & the Thunderbirds, since Wilson has taken up residence in Los Angeles). Jimmie Vaughan emerged from near-exile with a stunning solo record two years ago, but has reverted back into being a recluse. Most of the members of the classic Antone's House Band have gone their separate ways. Only W.C. Clark -- the one true link between Austin's black blues scene and its white step-sibling -- carries the torch that lit the halcyon days of the Seventies when Antone's pumped into the wee hours of the morning, always playing, always touring.

It may be the most famous name in Austin blues clubs, but Antone's had never been the only one. By the late Eighties and early Nineties, clubs like Pearl's, La Zona Rosa, Steamboat, and the Continental Club tapped into a lot of Antone's potential draw, not to mention Sixth Street clubs like 311, Jazz, Babe's, and other places supporting cover bands whose material probably included at least one T-Birds or Stevie tune. If you caught Lazy Lester one weekend at Antone's in 1991, Soulhat gigs probably paid for him to play.

Stevie had been Everyman with a Stratocaster, the younger brother who tried harder. He had given white blues individuality and personality. In one blinding flash of human error, it was gone.

Antone's had to evolve; the times and the competition demanded it. Visitors from Europe who come to Austin's blues mecca today may be baffled to wander in on the Scabs, but running a club remains a business. The world-famous home of the blues has monthly expenses to meet that don't go away and only grow, so it makes sense for them to book bands to attract a younger audience. If new clubgoers are attracted to Antone's by an Ugly Americans show, good. If it inspires them to come out for Miss Lavelle White, better.

This current crop of torchbearers plays blues for different, equally notable and remarkable reasons. The primary difference is that today's blues bands now are influenced as much by SRV and the T-Birds as they are by the old masters. Storyville bridges the old and new scenes with its ex-Double Trouble rhythm section and Malford Milligan's angelic vocals. Sue Foley doesn't pack the house the way she should, and eventually will, by fusing Strehli's cool grace with Barton's firecracker performances and a take-no-prisoners approach to blues guitar. One-time blues guitarslinger Ian Moore has shifted naturally into more rock & roll, and seems much more at home on the Steamboat stage than Antone's. Still, Guy Forsyth covers old-timey blues in the Asylum Street Spankers and lurks menacingly with style and panache into Kim Wilson's old harp-cat territory. Toni Price's country blues are staggeringly popular, and Gary Primich is not afraid to forego a bass player altogether on occasion in favor of what he called "that Hound Dog Taylor sound." Hound Dog Taylor. These are comforting words, coming from the new scenemakers.

So Austin's blues is most certainly not dead, even if the original white scene that created its reputation is gone. Maybe that scene was just finished with its mission: It had outgrown itself and was ready to metamorphose, to shed the skin that had so safely encased it. The hippie ethic included a noble and well-meaning notion, the idea that whatever is liberated should be given away to the most people possible -- power to the people. Austin's players who braved the blues frontier in the Cosmic Cowboy Seventies lived that notion, even if they felt alienated by the hippie mothership at the Armadillo World Headquarters. By the end of the Eighties, blues had eclipsed country as the sound of Austin, Texas, and Stevie Ray Vaughan & Double Trouble and the Fabulous Thunderbirds had become the standard for up-and-comers by giving Austin blues to a national audience.

Gone but not forgotten. In the Nineties, most of these newer bands are heirs to that Seventies legacy, as are the dozen or so clubs in town with blues-based bands. When the Victory Grill reopened on the Eastside last year, it seemed to indicate that the black community was ready to take back the blues; the current crop of talent and a revival of Eastside blues players is a healthy sign. If Antone's no longer has to uphold the standard for blues, that's not so bad: By its nature, blues has thrived in the shadows, much more so than the spotlight. And if it's harder than ever to get the gig because the competition's tough and the players good, well, ain't that the blues.